BRINGING TO LIGHT

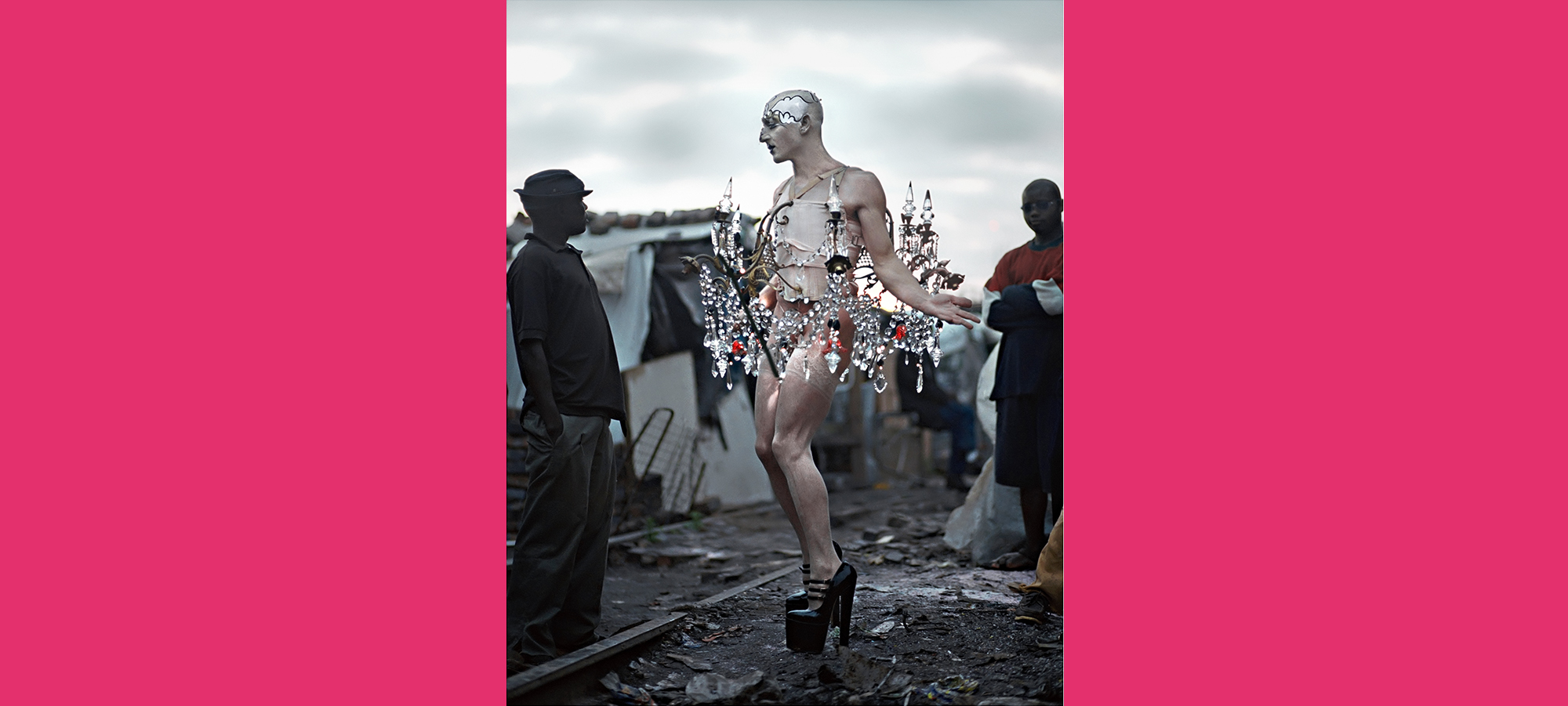

I’ve been looking back through the archives of the Djanogly Gallery to find works for #PrideMonth. One of the most memorable has to be this piece by Steven Cohen included in ‘Life Less Ordinary’, an exhibition of contemporary South African art. The image is a still from ‘Chandelier’, a film of a performance the artist (pictured) made in 2001.

Cohen is a gay, Jewish, white South African and broadly speaking his work addresses issues around marginalised identities.

The claim that art takes risks is used too often and too glibly but not in Cohen’s case.

His performances are confrontational and often made at some risk to his own personal safety. On more than one occasion they have landed him in the courts.

Click on the picture to open up a bigger view

For this work, Cohen, costumed in an illuminated chandelier, teetered on vertiginous heels into the Newtown township in Johannesburg. Contrasting opulence (white privilege) with poverty and degradation, the film records his encounter with the inhabitants of the camp. The performance coincided with the arrival of government workers tasked with demolishing and clearing the township and moving the resident population out. This was post-Apartheid South Africa but, as Cohen’s performance was intended to highlight, massive disparities still existed in wealth and opportunity in the country. Ironically, the site was being cleared for the construction of the Nelson Mandela Bridge.

Image: Chandelier, 2001 by Steven Cohen. Photo: John Hogg

©Steven Cohen. Courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

For further information on the artist and his work visit this page.

DISTANT VOICES

In 1992, Rictor Norton brought out a book that gloried in the title Mother Clap’s Molly House about gay subculture in eighteenth-century England. I remember picking it up – probably in Nottingham’s sadly missed Mushroom bookshop – and being intrigued by the statement on the jacket that

eighteenth-century London had more places where gay men could meet than existed there in the 1950s.

A ‘Molly’ was the derogatory name then given to homosexual men and, unsurprisingly, much of the information for Norton’s book came from court trials of the time and, in particular, from a raid on the establishment in question in 1726 from which we learn a great deal about what went on in the house ‘Mother Clap’ was keeping. It’s a fascinating piece of research.

What are perhaps rarer to find are any images of gay men from this period in the visual culture of the day. An exception is the group of music makers who appear in one of the scenes from William Hogarth’s famous ‘Marriage a la Mode’ series of engraved prints, a copy of which is owned by the University of Nottingham. They form part of a gathering in a lady’s boudoir but are actually incidental to the main action: an adulterous affair between the lady and her lawyer.

Click on the picture to open up a bigger view

On the far right-hand side of the scene the musical entertainment is led by an extravagantly dressed singer. The extra pounds he’s carrying suggest that he might be one of the fashionable Italian castrati then taking London by storm. Over his right shoulder a flautist accompanies his song. Next to them sits a delicate looking man drinking chocolate with his hair in rag curlers and to the left of him sits another figure whose exaggerated hand gesture seems designed to draw attention to the fan tied to his wrist. Hogarth litters his pictures with clues to their meaning and here the sexual orientation of this group is suggested in the subject of the painting that hangs on the wall behind them. It is the abduction of Ganymede by Zeus who in eagle form swoops down and carries off the beautiful youth. Hogarth makes his sly insinuation stronger by giving the flute player a beak-shaped nose and fingers that resemble the claws of the eagle.

A flattering portrayal of gay subculture it certainly isn’t and given the artist’s moral intention the group is almost certainly there to reflect poorly on the lady’s licentious lifestyle. Nevertheless, at a time when anything that deviated from sexual orthodoxy tended to be written out of history it offers a rare glimpse into the existence of an alternative world.

Image: Marriage a la Mode: IV, The Toilette c.1743 (detail) engraving by William Hogarth (1697-1764).

Collection: The University of Nottingham

For further information on this work visit our Out of Store blog.